The Venezuelan Diaspora Oganizations: The Exercise of Public Diplomacy

Ph.D. Tomás Páez (President of the Venezuelan Diaspora Observatory and the Global Venezuelan Diaspora Platform)

Abstract.

The Venezuelan diaspora, the largest in Latin America, consisting of 9 million people in 90 countries, shapes a “New Geography” of Venezuela. Citizens and their transnational organizations highlight the limitations of the nation-state concept. Their growing presence worldwide reveals the resounding failure of “21st-century socialism,” which is why the government considers them an enemy, treats them with hostility, denies their existence, and, in a show of xenophobia, excludes them from official statistics.

Official diplomacy, subordinated to the political and ideological interests of the ruling faction, runs counter to the diaspora; its allies are enemies of democracy and freedoms—autocracies and theocracies: Iran, Cuba, Nicaragua, China, Russia—countries that are off the radar of the Venezuelan exodus. The government’s rejection contrasts with the hospitality of the countries chosen by migrants, all of which are supporters of democracy. In these countries, over 1,300 diaspora organizations engage in “public diplomacy,” sharing democratic values and principles and denouncing the systematic violation of human rights in Venezuela.

In light of the void left by “official diplomacy,” due to the disregard for migrants and the conflictual or non-existent relationships with democratic countries, transnational diaspora organizations take on the responsibility of addressing their needs and expectations while maintaining ties with the institutions of their country of origin. Through their public diplomacy efforts, they forge the “Governance Strategy” of the diaspora and prefigure the future nature of foreign service. This emerges from a paradigm shift and more than a decade of work that has made it possible to establish a global public policy agenda, reinforced by the findings of the most recent studies coordinated by the Venezuelan Diaspora Observatory (ODV).

KEYWORDS: Associations, public diplomacy, official diplomacy, governance strategy, Trust

1. INTRODUCTION.

We embarked on the Venezuelan Diaspora Observatory (ODV) project in response to the bewilderment caused by an unprecedented and growing exodus, driven by our interest in understanding and explaining this migratory phenomenon. We explored the sociodemographic profile, the degree of social, economic, and cultural integration, the reasons for the decision to migrate, the intention to return, and the willingness to participate in the reconstruction of the country. The decision to migrate is individual, although the frequency of the reasons cited converges in identifying the model of “21st-century socialism” as the primary cause. It embodies economic deterioration, diminished purchasing power, scarcity, rationing, deinstitutionalization, the encroachment on basic human rights, property, expression, and information, as well as increasing legal and personal insecurity.

The enormous economic contraction of approximately 80% of GDP (Gross Domestic Product) and personal and legal insecurity transformed the country into a source of migrants, although it was unimaginable that the figure could reach 9 million people. Between 1999 and 2015, 120,000 people migrated annually; between 2016 and 2019, this number multiplied tenfold, soaring to 1,200,000 people per year. Since the onset of COVID and then during the post-COVID period, the figure contracted and, after a downturn, has resurged at about 500,000 people per year. More than 67% of migrants report having family and friends considering migration, indicating that the exodus could continue to grow [1].

The following table shows the high levels of distrust the diaspora has toward the government, in contrast to the trust placed in private enterprise, neighbors, and diaspora organizations in both host and home countries.

Comparative Levels of Distr13ust in Venezuela and Host Countries

| INSTITUTIONS | IN VENEZUELA | IN THE HOST COUNTRY |

| Natrional Government | 93.30% | 18.50% |

| Electoral Institution | 86.60% | 9.90% |

| Political Parties | 67.20% | 21.10% |

| Diaspora Organizations | 18.00 % | 10.70% |

| Private Business | 13.80% | 7.00% |

| Neighbors | 8.00% | 12.30% |

Source: ODV 2024

Despite the reality and magnitude of the diaspora, the Venezuelan government ignores it in an act of hostility and xenophobia. This was evident in 2018 during a meeting in New York at the United Nations, where it faced astonished recipient countries. More recently, it disregarded the right enshrined in the Constitution by calling for a referendum from which the diaspora was excluded. Just a couple of months ago, downplaying information from statistical institutes in neighboring countries, academic institutions, and international organizations, it attempted to minimize the magnitude of the exodus.

The diaspora has been de facto marginalized from official state-to-state relations. The Venezuelan government disavows the “non-existent diaspora,” and if that were not enough, it is at odds with or maintains strained relations with the governments of the countries receiving Venezuelan exiles. The diaspora is supported by a network of diaspora organizations practicing “public diplomacy,” posing a challenge to “official diplomacy.”

Diaspora organizations engage in cultural diplomacy, building and maintaining relationships, and negotiating with institutions in the host regions. They forge alliances, strengthen and expand communication, and influence local, national, and international arenas. With the “New Geography,” a novel “Map of New Actors” is being created, comprising individuals and diasporic associations endowed with reputation and trust. Their actions confirm that dialogic public diplomacy is possible, positively impacting Venezuela’s international reputation, with new actors emerging in the field, countering the pathological pugnacity of official diplomacy.

They counter official diplomacy through new communication technologies and transnational networks, operating beyond the confines of states. Daily meetings and workshops occur among these organizations, most of which are small and medium-sized, with limited resources yet formidable influence, shaping public opinion and crafting priority agendas.

The map of actors expands and diversifies as the exodus increases, intertwining with civil society organizations in the old map. The government represses civil society, persecutes its organizations, and employs an anti-NGO legal framework, condemned by organizations such as Amnesty International as a state policy aimed at undermining human rights and destroying transnational ties among organizations.

The official diplomacy’s animosity toward the diaspora and its organizations extends to initiatives from governments and international organizations aimed at raising funds to address the urgent needs of the diaspora. Instead of gratitude for the effort, promoters are accused of being scammers. The government’s hostility toward the diaspora knows no bounds.

Organizations have operated for several years and decades, establishing alliances and forming networks. Initial isolation is overcome through collaboration. They listen, coordinate, formulate, and execute projects. They document and disseminate information through available media about the country’s situation. They also promote values and culture, acting as “ambassadors and attachés” in commercial, cultural, and scientific domains. Their actions transcend official diplomacy.

The new map of actors wields power, implanting a narrative that contradicts and refutes the one imposed by the government. They disseminate and expand it through portals, media outlets, and existing communication applications. They engage in public debate with studies, documents, reports, videos, films, literature, theater, music, and humor—a viral effort that connects in a horizontal and decentralized manner. Their actions forge governance strategy and defend human rights and liberal democracy: they envision change and work to realize it.

The first global study [2]required filling the information gap regarding the number and distribution of the diaspora worldwide, compelling us to condense two investigations into the text presented in 2015. We began the project by establishing the approach, challenging beliefs and prejudices in political and academic circles. We present them in the following table, with prejudices and beliefs in the left column and the project principles in the right column.

| BELIEFS, PREJUDICES, AND FALLACIES – PROJECT FOUNDATIONS | |

| BELIEFS, PREJUDICES, AND FALLACIES IN POLITICAL AND ACADEMIC CIRCLES: LATIN AMERICA AND GLOBAL | PROJECT FOUNDATIONS |

| Brain drain–brain theft | Circulation of people, knowledge, information, and capabilities |

| Rich countries win–poor ones lose. Losers-Winners | EVERYONE WINS: migrants and host and origin countries |

| Migration crisis. Migration as calamity | Migration as challenge and opportunity |

| Unemployment–destruction of wages | Employment, entrepreneurship, and business |

| Impediment to development | Migration promotes development |

| Destruction of identity | Plurality and diversity |

| Potential-dangerous | Human fact–cultural expansion |

| State, laws, and norms: for return, to seize remittances | Unforeseen consequences of laws, some known, others unexpected |

| Only Official diplomacy | Public diplomacy |

Prejudices manifest in various ways and are equally distributed across origin and host countries. The government’s prejudices are glaring, to the extent of denying the fundamental right to identity, a prerequisite for exercising other civic and political rights, violating international and bilateral agreements regarding the rights of pensioners and retirees, and showing general neglect toward its citizens[3]. In response, associations of retirees and pensioners in the diaspora have formed. They denounce violations of international agreements and propose initiatives to resolve issues in host countries.

The government denies the political right of the diaspora to register and update their information in the Permanent Electoral Registry (emphasis added), a necessary condition to exercise the right to vote. The other right, to be elected regardless of residence, has been omitted from the country’s Constitution. Diaspora associations have documented and reported this violation to political parties and parliaments in host countries, conducting mobilizations demanding the right to register, as denying this is a transgression that undermines democracy.

Another manifestation of indifference and disdain toward citizens, particularly those in the diaspora, is seen in the slowness and costs associated with obtaining passports. The price is among the three most expensive in the world at $200, following Lebanon ($795) and Syria ($330). The worst of the prejudices and xenophobia—ignorance of the existence of others[4]—has been accompanied by hurtful phrases and arguments, using epithets that incapacitate the government from relating to them. Diaspora organizations have denounced the situation and requested recognition of expired passports, which several countries now accept.

A widespread prejudice in Latin American and global academic and media circles associates migration with brain drain, going so far as to define the exodus as “brain theft,” contrasting loser and winner countries. In host countries, we find two extremes: those who oppose immigration and those who favor it.

Among the former, prominent prejudices are present in the current political debate, with no expiration date and few ties to reality: they destroy “national identity,” a notion in which individual differences disappear, they ruin employment and wages, culture, foster crime and theft, and drain the welfare state.[5] Supported by data, perspectives on “human capital circulation” and the virtuous circle of migration and development are developed: demographic bonus, flow of ideas, innovation and productivity, contributing more than they receive, human rights, and a factor of progress.

2.- VENEZUELAN DIASPORA OBSERVATORY

Having presented the paradigm, vision, mission, and goals of the project, as well as the perspective from which we understand public diplomacy, it is worth briefly recounting the history of the project. The findings provide the basic inputs for designing the strategy, including understanding the diaspora’s willingness to participate in the reconstruction of the country they had left. At the same time, we formed the initial team with which we began the first study.

The organizational structure consists of a network of organizations with legal status in Latin America, Europe, and the United States, as well as a dense network of partnerships with public and private institutions and civil society organizations[6]. The involvement of individuals and organizations made it possible to address the gap in official information, a deficiency that severely harms democracy, as information is a public good essential to it.

As the reader can imagine, this was no easy task, but it was ultimately rewarded with knowledge of the magnitude and distribution of the diaspora across continents, countries, and cities[7]. The web of relationships built from the start facilitated the global distribution of questionnaires, in-depth interviews, life stories, and focus groups—the set of tools applied in the research.

The information gathered included data on their associations and organizations. Thanks to these, we began a global tour, local, national, and regional meetings, which provided valuable insights into their projects, expectations, and areas of interest. Since 2016, we have established partnerships and created regional observatories in Venezuela and around the world. In 2017, we launched a pioneering program on Venezuelan TV and radio, a weekly meeting aimed at connecting organizations across five continents[8]. In 2020–2022, we launched another weekly program on the same station, «Diaspora and Environment,» which featured over 60 organizations and specialists focused on environmental issues.

The third stage arises from the public diplomacy actions of the organizations to establish the Platform and the Venezuelan Diaspora Institute (IVD), providing continuity and support to the transnational organizations of the diaspora[9]. The activities carried out with the diaspora and their organizations have consolidated the narrative and a new way of understanding and addressing the Venezuelan exodus.

The change has not been easy. On the one hand, there is denial of the diaspora’s existence, and on the other, the use of stigmatizing labels, generalizations, and affirmations: all are exiles, refugees, displaced persons, and the most common, «migration crisis.» This categorization turns migration into the problem, when it is actually the consequence of the deep economic, social, institutional, and political crisis in Venezuela. The real issue to solve is not migration but its causes, which is why our slogan has been: «The diaspora is not the problem; it is part of the solution.»

The results support the change in perspective we have proposed. Events held by diaspora organizations under the title «The Role of the Diaspora in the Reconstruction of Venezuela,» and the networks and projects developed by diaspora organizations in various areas—entrepreneurship, communication, mental health, environment, higher education, etc.[10]—show a shift from viewing the exodus as a calamity to seeing migration as an opportunity, an expansion of borders and cultures beyond their origins. Initiatives by institutions in Venezuela to leverage the networks built by the diaspora confirm this shift.

3.- REASONS FOR THE EXODUS. CIVIL SOCIETY, DIASPORIC ORGANIZATIONS, AND NEW PUBLIC DIPLOMACY

The «Cumbre Vieja» volcano in La Palma forced the evacuation of thousands, destroying businesses, homes, crops, and the savings of many families. The tragic data from natural disasters pale in comparison to those caused by humans in Venezuela, through the imposition of «21st-century socialism,» which Héctor Silva aptly defined as a model of insanity. This system mirrors the fate of Soviet socialist countries, Nicaragua, Cuba, and China, and one undeniable feature is the creation of diasporas.

Another characteristic of this model is economic precariousness. Estimates by specialists such as Ricardo Hausmann highlight the scale of the collapse. The drop in GDP and GDP per capita (2012–2018) is sharper than that experienced during the Great Depression in the United States (1929–1933) and worse than in Russia and Cuba. Paula Rossiasco, a senior specialist at the World Bank, asserts: «The economic crisis in Venezuela is unprecedented in Latin America and the largest in the region and the world in the past 50 years, with higher inflation and GDP contraction rates than countries at war. This poses a direct threat to life, security, and freedom.» This period will go down in history as a dark and grim era, one of unimaginable backwardness.

It shares with all forms of real socialism the arrogance of autocrats and their bizarre projects. Stalin had his Arctic train, Castro his super milk-producing cow, Mao exterminated sparrows to end hunger, and Chávez pursued the Southern Gas Pipeline. The latter, with his total disdain for individuals, property, and the market system, nationalized everything he could, even State buildings, and expropriated what he shouldn’t have. His capricious overreach has cost Venezuelans over $20 billion in damages[11].

In an attempt to eliminate private property, the state used its purchasing power to impose collective production models (cooperatives, social production companies, communal enterprises), with results that were costly and failed. The goal was to replace the democratic system with the Soviet model or Cuba’s Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs), which they defined as the Communal State[12]. I once heard someone say that socialism is a degenerative disease that can only be reversed with high doses of private property, market, cooperation, and competition, as seen in China, Vietnam, and most Eastern European countries.

This model accepts only submission, and dissent is seen as treason. It fosters a «survival of the fittest» mentality where the other is an enemy or potential informant, eroding solidarity and cooperation. Information becomes opaque, turning into propaganda or simply disappearing, as in the case of the diaspora. Media outlets quickly learn to self-censor, as criticism leads to closure, expropriation, or confiscation. The government tries to give meaning to the meaningless, as seen in the derogatory labels used to discredit the diaspora: «gullible fools,» «toilet cleaners,» «bioterrorist weapons.»

The disdain for the diaspora reached its peak during the recent referendum[13]. Despite constitutional guarantees of the diaspora’s right to participate, the consultation ignored them, a blatant violation met with little protest. It is up to migrants and their organizations to reverse this bleak landscape of mistrust.

Official diplomacy plays on a geopolitical chessboard disconnected from Venezuela’s history and in open opposition to the democratic countries of the West. Instead of a state policy, it pursues an ideological one, a party policy, and a diplomacy of expelling diplomats. The most recent expulsion targeted the staff of the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. A long list of ongoing confrontations and diplomatic dismissals includes representatives from the European Union, Colombia, the United States, Spain, Brazil, Canada, European parliamentarians, and Reporters Without Borders.

Public diplomacy is exercised by the diaspora, operating on a geopolitical chessboard contrary to that of the government. The new map of actors in Venezuela’s «New Geography» shapes the Governance Strategy, dissolving the division between «those inside and those outside» and blurring conventional borders. A core difference between the two diplomacies lies in their objectives. Public diplomacy seeks to preserve democracy[14], while official diplomacy aims to undermine and destroy it, supporting those with similar goals in Spain, France, Latin America, and the Caribbean.

Eighty-eight percent of migrants have family in Venezuela, with over a third receiving financial support from the diaspora, maintaining constant contact through various social networks, particularly WhatsApp[15]. These networks enable global interconnections and transnational social ties that challenge the narrow limits of the nation-state. The organizations maximize their social and political efficiency, establishing agreements and work agendas that bypass the government, whose conditions limit the diaspora’s impact in both host and origin countries.

In the recent presidential elections on July 28, 2024, the government prevented voting, but it could not stop migrants from participating in the electoral process: in conversations with family and friends, meetings with organizations and civil society representatives, and discussions in various social media groups. These activities are a major headache for the government and official diplomacy.

The organizations act as active political actors, with their documents, information, reports, and mobilizations fueling devastating reports that expose the country’s reality in international forums. This reality forces representatives of the democratic alternative to rethink the role of the diaspora and its organizations in the foreign service.

Diaspora organizations are registering human rights violations in Venezuela with the International Criminal Court (ICC). They document these abuses, build virtual museums exhibiting the torture and dire conditions of political prisoners—many of them children and young people. Diaspora associations, along with political party representatives defending democracy, promote statements from parliaments and governments in host countries demanding respect for human rights and freedoms.

Individual organizations and groups in specific sectors develop projects and support initiatives by international organizations. Plans with local institutions in Córdoba, Argentina, in Valladolid, Spain, in Lima, Peru, and regional initiatives in partnership with the International Organization for Migration (IOM) focus on entrepreneurship and communication. They also carry out local and global mobilizations in defense of democracy in Venezuela, holding meetings at universities and centers like La Maison de l’Amérique, informing and showcasing videos and shorts documenting Venezuela’s environmental degradation.

Migrants try to escape from the government, which persists in harming them as it does with all citizens. The pension for retirees and pensioners residing in the «conventional geography» is less than $3, and since 2015, those who moved farther away, to the New Geography, violating international agreements, have not received any pension. The affected migrants, several tens of thousands, have organized and, in addition to filing complaints, propose solutions. Journalist organizations are tracking the looting of resources owned by Venezuelans, identifying those responsible for the networks of what Anne Applebaum calls «Authoritarianism Inc.»[16],

The emerging foreign service, which will arise with the change in government, must necessarily recognize and institutionalize dissent within the foreign service, as a way to show its democratic and inclusive nature. It is necessary to listen to, understand, address, and integrate the millions of ambassadors, investors, and commercial, technological, and cultural attachés into Venezuela’s development. Those who imitate the current foreign service are mistaken: democracy is contrary to uniform thinking, and the reconstruction of the country requires a monumental, comprehensive, and plural effort.

Civil society organizations possess valuable and high-quality information about the localities and cities where they currently reside. They establish ties with local organizations and institutions and with their counterparts located in the “conventional map of Venezuela.” Examples of this are networks of organizations focused on the environment, health, engineering, entrepreneurship, freedom of expression, and civic and political rights.

Their actions have allowed them to earn leadership, reputation, trust, and credibility from everyone. This hard-earned achievement cannot be replaced by political or economic impositions. Therefore, those who have attempted to impose agendas without consulting people and their organizations are mistaken. Those who act in this way view citizens as stepping stones in their career. Imposition, always arrogant, plays in a field different from democracy and the practice of CITIZENSHIP AND POLITICS. Building «transnational citizenship» and engaging in politics requires consulting, listening, exchanging ideas, and acting. The opposite is anti-politics, which grants circumstances, and the deterioration of the situation, the characteristics and properties of change inherent to human beings.

The diaspora, as we have said, is a diverse and plural phenomenon, as are its organizations. It is the opposite of monolithism and uniform thinking. They are not subordinated to the designs of a party or group of parties, especially when the suggested path is «not missing the opportunity to miss the opportunity.»

Where they reside, they defend political rights, promote democratic attitudes, and denounce anything that threatens freedoms and the individual. These organizations are aware of both their needs and their capabilities[17]. Previous paragraphs have mentioned several examples: global mobilizations in defense of the vote, denouncing obstacles to diaspora participation in elections, in the global consultation of 2017[18], and the most recent one in 2024. They make their own decisions and do not ask others to decide for them.

Those who advocate and defend democracy and freedom are the most interested in strengthening the transnational associative fabric and the actions of «public diplomacy.» The democratic alternative requires the participation of everyone and cannot rest on diminished capacities for action and communication. Their interest is to connect with as many Venezuelans as possible and regain trust.

Under “21st-century socialism,” the separation of powers is progressively disappearing. As confessed by the former president of the Supreme Court of Justice, in the new model, justice obeys the executive[19]. It is a sinister project that can only function through imposition, force, and persecution. One of its latest initiatives, weaving threads of absence, involves dismantling civil society associations. Only those submissive to the government party faction will be allowed to operate.

4.- PUBLIC DIPLOMACY AND DIASPORA GOVERNANCE STRATEGY

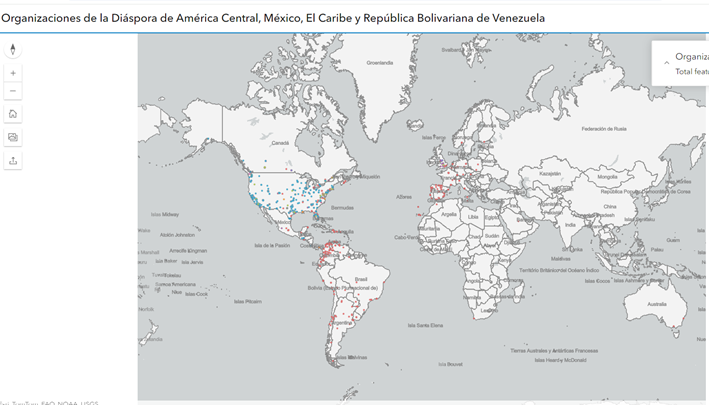

The Observatory (ODV) has established itself as a dense network of alliances with organizations and individuals from the diaspora. It has loyal representatives in various countries [20]and allied institutions located on the «conventional map of Venezuela»[21]. The ODV systematically monitors the diaspora and its organizations and associations, fostering mutual understanding, shared learning, and the development of broader and more impactful projects, such as those mentioned in the areas of entrepreneurship and freedom of expression. Some of these initiatives are reflected in the following world map[22].

The diasporic organization is the fundamental unit of the strategy[23]. These organizations form the threads of the fabric, the large web of transnational organizations, always connected and grouped around areas and topics of shared interest. The initial global network has expanded with the creation of new chapters of the Observatory in countries throughout the region, extending the network of alliances and projects with diaspora associations[24].

As we’ve seen, these organizations engage in «public diplomacy» in various forms and through diverse means. They have created radio and TV spaces, communication platforms, migrant support centers, and more. They present and explain the country’s crisis in universities, media outlets, political parties, parliaments, and international events. One example of this is the ODV’s participation in the Global Diaspora Week of the IOM[25].

Here is an overview of the activities they carry out in the field of public diplomacy:

a.- They document and disseminate human rights violations across the globe. They monitor institutions such as the International Criminal Court and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. They organize mobilizations and virtual presentations of torture centers in Venezuela, and provide data that informs reports by the Human Rights Commission and the United Nations Independent Experts Mission.

Their documentation, denunciations, mobilizations, and presentations include violations of civic and political rights, the neglect of pensioners’ and retirees’ rights, environmental destruction in Venezuela, and more.

b.- Diaspora organizations fill the void left by official diplomacy wherever possible. Venezuelans, particularly migrants, find it difficult to obtain documents such as passports due to high costs and bureaucratic delays. The diaspora has protested against being treated as second-class citizens or marginalized. A clear example is the recent presidential election on July 28, 2024. The only requirement for any Venezuelan citizen to register, update their information, and vote is a national ID, even if expired. However, for Venezuelans in the diaspora, additional conditions were imposed: a valid passport, registration with the consulate, and proof of legal residence. This is far more than what host countries require and highlights the contrast between the hospitality of host countries and the hostility from their country of origin. This discriminatory treatment excluded more than 6.5 million people from voting.

c.- Official diplomacy operates without and against the diaspora and its associations, which bear the responsibilities abandoned by the government. They guide and inform newcomers, implement social and economic integration programs, act as intermediaries with local and national institutions, defend human rights, and, in the case of professional organizations, advocate for their members (doctors, engineers, nurses, economists, pensioners, retirees, students, etc.).

d.- Their activities enable the internationalization of Venezuelan organizations and companies. An example of this is the creation of a chapter of the Academy of Engineering and Habitat in Spain and chapters of Médicos Unidos de Venezuela. They also undertake initiatives to raise funds to support organizations, people, hospitals, and schools in their country of origin.

e.- The organizations also serve as sources of information on the supply and demand of jobs, helping place migrants in regions and cities to avoid depopulation.

f.- The diaspora organizations and the Observatory contribute to and participate in creating networks between universities in host countries and those in Venezuela. Examples include Spain, Brazil, Argentina, Peru, Colombia, and the United States. They also establish agreements with diaspora groups and observatories from other countries, such as Brazil and Portugal, and assist in creating diaspora observatories in other countries, such as FLACSO in Argentina.

g.- In the face of the deafening silence and hostility of “official diplomacy,” the diaspora supports and accompanies humanitarian initiatives from organizations in host countries. In Riohacha, Colombia, it was the civil society of that country, along with the local mayor’s office, that established a cemetery to serve deceased members of low-income Venezuelan families.

h.- Official diplomacy has abandoned cultural promotion, but thanks to the public diplomacy efforts of diaspora organizations, it has been possible to recover culture as Venezuela’s identity card and improve the country’s positioning in the world. Cultural exchange plays an important role in international relations.

Diaspora organizations promote culture and gastronomy in its various forms. They celebrate Venezuela’s most emblematic religious festivals wherever they now reside: the Virgins of Valle, Coromoto, Chinita, and Divina Pastora. They have established global days to celebrate Venezuelan cuisine, such as the Arepa and Hallaca festivals. The impressive musical movement that began in Venezuela during the democratic period in 1975 has spread worldwide, forming diaspora orchestras in Colombia, Argentina, Spain, and more. Artists have created «teatrozoom» and humor festivals organized by diaspora associations, all public diplomacy initiatives outside of official institutions.

i.- The diaspora and its organizations defend democracy and freedoms. Research on the diaspora’s commitment to democracy reveals eloquent findings, as shown in the following graph.

In previous paragraphs, we have described the numerous activities carried out by these organizations that demonstrate their commitment: documentation, mobilizations, meetings, talks, workshops, etc. In this chapter, we have incorporated data from recent studies: that of diaspora organizations and associations (IOM-ODV), from which the «Management Manual» [26]emerged, and research on the propensity for participation of Venezuelan migrants. We have also included the study of associations and public diplomacy of Spanish migrants in Venezuela[27].

As we have pointed out, they group together based on common and shared interests. They promote education, leadership, democracy, freedoms, culture, and the defense of human rights, both in Venezuela and globally. They formulate agendas with local governments, political parties, companies, and international cooperation organizations to foster the social and economic integration of new arrivals. They draft proclamations and encourage parliaments and political parties to speak out in favor of democracy, free elections, and human rights in Venezuela.

They actively combat the prejudices previously mentioned and craft narratives to counter xenophobic discourses. They study and quantify their contributions directly or through reliable organizations and institutions. The documentation of their contributions goes beyond the economic sphere, incorporating contributions to the political, social, and cultural realms. Their actions generate resilience to prevent similar destruction from occurring in Venezuela.

The official diplomacy, hostile to private property and enterprise, operates in stark contrast to public diplomacy, which seeks to connect with the business fabric of host countries and to promote the creation of new businesses among migrants. They view businesses as tools for creating wealth, employment, economic integration, and social cohesion, and as one of the antidotes to totalitarian models, as they strengthen individual autonomy and recognition[28].

Migration flows occur between regions, at both origin and destination. Ideas flow with migrants, made of the same substance as the people themselves, forming an immense stock of human capital, the most important asset available to companies and countries. They formulate agendas and implement policies connected to global political issues, for instance, denouncing the presence of gangs and armed groups from neighboring countries and the Middle East in Venezuela.

The consequences of official diplomacy can be very harmful to the country. Consider this example: in 1999, Venezuela suffered a natural disaster—floods and landslides known as the Vargas tragedy, which claimed thousands of lives. The Minister of Defense and the head of Civil Defense requested assistance from the United States, whose response was immediate. The President, in an act of hostility and inhumanity toward Venezuelans in need of support and toward the U.S. government, rejected their help.

From the outset, official diplomacy has sown divisive lines between friends and enemies. There is no room for the disappearance of such limits, characteristic of any regime with totalitarian ambitions: “you’re either with me or against me,” and submission must be absolute. The cultural sphere is emblematic of these boundaries. Those who refuse to submit, whether actors, singers, comedians, or musicians, are silenced, while loyalists are funded and promoted. In this attempt at division, no space for truce is acknowledged—not even at the time of physical disappearance.

The diaspora and its organizations represent the voice of those the government silences and scorns. The «public diplomacy» they practice expresses sensitivities different and divergent from those of the official stance, particularly in the realm of human creativity[29]. Instead of supporting and relying on the magnificent efforts of diaspora organizations, the government opts to fund those who confront and persecute them in countries and regions where they have ideological allies.

The fact that the government views education as a tool for indoctrination and ideological manipulation disqualifies it from establishing relationships with the scientific and academic diaspora. Official diplomacy promotes «revolutionary tourism» among professors and students from its allied countries. They offer hotels, excursions, and beaches to gain support for their project.

Scientific and technological attaches of public diplomacy make efforts to denounce the state of education and human rights violations in Venezuela. It is not easy to explain the country’s situation, and for many, it is even incomprehensible. In one article, I cited—with permission from the affected professor—the case of CLACSO (Latin American Council of Social Sciences), an institution that voiced support for the Venezuelan President, as well as ideological skirmishes in other social science organizations, and the unjustifiable silence of environmental organizations regarding the devastation of the Venezuelan Amazon.

In the academic field, another debate is necessary. The dominant explanation attributes the situation to capitalism, with «neoliberalism» as the preferred target—especially when labeled as «savage» (Bernard-Henri Lévy rightly questions the absurdity of that term). Neoliberalism is blamed for creating inequality and poverty, which for them, are the reasons behind all migration, or «escape,» as they prefer to say—though others opt for the term «brain drain,»[30] as if human capital belonged to them.

Despite the widespread use of this linear explanation—neoliberalism, poverty, inequality, migration—the events in Venezuela, Cuba, China at one time, and the countries of the Soviet bloc refute this assumption, which has evolved into dogma. This deeply ingrained belief does not explain the exodus caused by armed projects that tried to impose the Soviet or Chinese model by force in Latin American, European, and African countries.

Socialism, as someone once said, did not collapse with the fall of the Berlin Wall; it did so when the wall was built to prevent citizens from exercising their right to mobility, as enshrined in the 1948 Declaration of Human Rights. Under this model, the individual disappears, as Sophie Heine argues. The individual is replaced by collectives and communes, and with the eclipse of the individual, their rights are annihilated.

The performance of these organizations has had to face multiple challenges simultaneously:

The xenophobia and disdain of the Venezuelan government toward Venezuelan migrants and their organizations.

The use of the diaspora as a political weapon rather than recognizing it as a social reality for the exercise of politics.

This latter point reflected in the intellectual poverty and complacency of those who should be the first to denounce the abuses of a regime that stifles freedoms and democracy.

Confronting newly polished, paralyzing catastrophic views, which see deterioration and crisis as reasons for change—a mechanical vision that halts the exercise of public diplomacy.

Diaspora associations act—they engage in politics, not «collapsology,» as practiced by those who believe that sending remittances, medicines, food, and equipment to family and friends benefits the regime and delays change. The data presented earlier regarding the destruction of the country refutes this belief. With actions, and as the saying goes, “actions speak louder than words,” these associations demonstrate their commitment and willingness to continue being part of the process of restoring democracy in order to rebuild the country[31]. They engage in politics and public diplomacy. They act ethically by setting agendas, driving change, and transforming reality

In their actions, they confront a government that daily reduces the space for freedom of expression and civil society. In Venezuela, speaking out against the government can lead to imprisonment or death[32]. In their work, they preserve the democratic history in which they were formed before the current regime came to power in 1998. As we have pointed out, they cooperate, engage in dialogue, and establish complex organizational networks[33].

The organizations are plural, heterogeneous, and exhibit a diversity of organizational forms: chats among high school and university alumni, work groups, neighborhood associations, homeowners’ associations, and the networks mentioned in this article. It is an enormous challenge to assist these organizations, whose characteristics we have highlighted. A shift in perspective is necessary, one that is more holistic and collaborative, with new criteria and methodologies from international cooperation bodies and large private sponsors.

This challenge is similar to what the financial sector has faced in serving self-employed workers, micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises. Simplifying access procedures without sacrificing security and guarantees that resources will be used appropriately is essential.

As I write this article, in the clearest Nazi-style manner, Rocío San Miguel, a well-known social leader, and her family have been irregularly detained despite being under the protection of a ruling by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. Additionally, the government expelled the staff of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights from the country. In the face of the silencing imposed on Venezuelans by the government, the public diplomacy exercised by the diaspora and its organizations takes on even greater significance.

The government’s authoritarian project demands the colonization and subordination of the judicial and legislative branches to the executive power. By violating the legal framework, the government has appointed members of the judiciary, allowing it to administer justice as it sees fit, thereby politicizing the judicial system. This has subordinated the judiciary to other branches, eliminating the principle of checks and balances, signaling the demise of freedoms and democracy[34].

Through public diplomacy, organizations collect and distribute medicines, equipment, and food to children, youth, adults, hospitals, and schools in Venezuela. The distribution involves the organizations and networks of organizations operating within the country.

The heterogeneity of the diaspora cannot be boxed into simple categories or elementary generalizations. Thomas Mann warns us about those who make hasty judgments about complex realities they barely understand. Trying to fit over 9 million Venezuelans into simplistic schemes prevents an understanding of the phenomenon and, worse, obstructs the design of policies to meet the various needs, expectations, problems, and potentials of the diaspora.

At this point, what Hannah Arendt expressed about transnational citizenship becomes relevant: a citizenship free from the impositions of national majorities, differential conditions, and particularist identities, to define an open horizon where post-national citizenships can assume the unavoidable banner of «the right to have rights.» This is not because it is regulated by a specific sovereign state or the community of nations, but because it is demanded by the human condition, the political freedom to be conquered, and the will to act in the public sphere to restore this primordial right from which all others stem. This is the exercise of citizenship that the diaspora and its organizations engage in, defending their rights. Their defense and achievements are attributable to the establishment of political communities, formed by citizens committed to protecting human rights.

Social reality unfolds amidst uncertainty and change, making it impossible to predict what will happen. Adding to this is the complexity and multi-causality of the migration phenomenon. The economic and social collapse has degenerated into sterile confrontation, political and ideological persecution, and now the government has decided to hammer the final nails into democracy’s coffin by expelling the United Nations mission and ignoring the July 28 election results. Furthermore, without hiding its Nazi character, the regime is now detaining the families of social leaders.

The destruction, the magnitude of poverty, and the ideological orientation of official diplomacy challenge the imagination. Its multifaceted nature prevents us from grasping the scale of effort and resources, both financial and human, that will be needed to restore democracy and rebuild the country. This must be done with everyone, including the human capital of the diaspora.

The path has been laid, and the foundations of the diaspora’s governance strategy have been established. It intertwines current public diplomacy with official diplomacy, which will need to be restructured, redefined, and adapted to the new reality. This requires a shift in perspective, understanding that its effects, as Clemens I. argues, exceed those of trade or financial liberalization and that it contributes, as Robert Guest affirms, to the free flow of ideas.

In 1936, the Venezuelan state approved the legal framework and institutions to attract migrants. Today, 90 years later, a new institutional framework is needed, which has been prefigured by the diaspora’s organizations and work. Civil society, the private sector, businesses, and decentralized institutions must act as key players. This strategy must be based on respect for autonomy and plurality, principles that underpin democracy, thereby valuing cooperation over the tiresome strategy of confrontation.

In this year 2024, on July 28, the presidential elections took place, and in 2025, a new parliament will be elected. In the first election, the diaspora was denied the right to vote, with only a few thousand citizens allowed to register. Next year’s election excludes the diaspora altogether, in violation of the constitution, breaking international agreements that protect the right of any citizen to vote and run for office, regardless of residence.

The government attacks the diaspora’s right to engage in the public sphere and exercise citizenship through voting. The vote is a key element of political participation; it allows for the choice between options and the exercise of popular sovereignty. The vote offers the possibility of change without bloodshed. Through public diplomacy, organizations have made significant efforts to defend these rights: identity, registration, and voting.

Restoring democracy and freedoms is a necessary step in rebuilding the country, which, as we understand, will never be the same as before. As we have said, social life unfolds amidst change and uncertainty. The diaspora has acquired new skills, competencies, knowledge, contacts, and networks that will be extremely useful for developing both their places of origin and destination. In the process, it will be necessary to overcome walls and build bridges, defeat the hatred propagated by the regime, and restore the trust needed to advance through global cooperation.

5.- CONCLUSIONS

Official diplomacy is subordinated to the political interests of the government and does not represent or advocate for the interests of its citizens, particularly those of the diaspora, whose existence it denies and ignores. Instead of building bridges and dialoguing with those who have migrated, with the host governments and international organizations, it detaches itself, withdraws, and remains silent. The organizations created by migrants represent their interests and expectations, engaging with the institutions of host countries and international organizations. In doing so, they lay the foundation for future diplomacy.

The public diplomacy of diaspora organizations builds a geopolitics contrary to that promoted by official diplomacy. The latter, besides not embodying the expectations and aspirations of migrants, personifies distrust. Diaspora associations act as intermediaries, representing those who have migrated and those «left behind.» They have demonstrated their capacity to understand the political and social culture of host countries and to forge fruitful relationships.

Unlike official diplomacy, which thrives on conflict, public diplomacy promotes cooperation, business alliances, and joint efforts in science, technology, and culture. Participation in international forums brings Venezuela’s critical situation to the global stage and fosters vigorous action to ensure the world remains engaged.

Migrants expand culture beyond borders, learning firsthand about the multiple policies of host countries to establish relations with their diasporas: defending their citizens wherever they reside, facilitating the exercise of human, social, and political rights, creating mobile consulates, and much more. Public diplomacy may not be able to resolve some issues, such as those related to identity documents, but it does much to build personal, institutional, and business networks of enormous importance for the restoration of freedom, democracy, and the reconstruction of the country.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arendt, H. (1951). The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace & Company.

Ascanio Sánchez, C. (1994). Associationism as an organizer of differences: an anthropological approach to recent Canary emigration to Venezuela. In XI Coloquio de Historia Canario Americana (pp. 135-160). Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Cabildo Insular.

Dávila Mendoza, T. D. (2014). Between nostalgia, diversions, and changes: Spanish associationism in Venezuela, 1930-2000. In The Associationism of the Venezuelan Diaspora: A Historical and Contemporary Approach (pp. 197-214). Universidad Central de Venezuela.

de Gasparini, L. M. (1994). Dictaduras y política migratoria. El caso de Venezuela en la década de los cincuenta. En XI Coloquio de Historia Canario-Americana (387-399). Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Cabildo Insular.

Ecoanalítica (varios años). Véase https://ecoanalitica.com/

Gallegos, R. (1949). El forastero. Caracas: Editorial Araluce.

Gammeltoft, P. (2002). Remittances and other financial flows to developing countries. International migration, 40(5), 181-211.

García Gómez, Mª T. (1994). La emigración canaria y su aporte al proceso democrático de Venezuela. En XI Coloquio de Historia Canario-Americana (373-385). Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Cabildo Insular.

Guest R. (2012). La demografía, la democracia y el capitalismo global. El Cato.org. Disponible en: https://www.elcato.org/la-demografia-la-democracia-y-el-capitalismo-global.

McBeth, B. S. (1983). Juan Vicente Gómez and the oil companies in Venezuela, 1908-1935. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Observatorio de la Diáspora de Venezuela (2023). Varios años. Informe de la diáspora en el mundo. Madrid: mimeo.

-(2023) ODV-OIM. Estudio de las organizaciones de la diáspora y su papel en el proceso de integración social y económica. En proceso de edición.

-(204) ODV Estudio de la propensión de la diáspora a ejercer los derechos cívicos y políticos. En proceso de edición

OCEI. (1997). Índice de Desarrollo Humano en Venezuela. Caracas.

Organización Internacional para las Migraciones. (2013). Diásporas y desarrollo: tender puentes entre sociedades y estados. Conferencia ministerial sobre la diáspora. Ginebra.

— (2019). Glosario de la OIM sobre Migración. Ginebra.

—. (2022). R4V “Response for Venezuelans” or “Respuesta a Venezuela”. Plataforma de Cooperación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. Ginebra.

Organización Internacional para las Migraciones y Migration Policy Institute (MPI). (2012). Hoja de Ruta para la participación de las diásporas en el desarrollo. Ginebra y Washington: OIM y MPI.

Páez, Tomás. (2019). The role of the Diaspora in the Reconstruction of Venezuela. Revista de Occidente, 458-459, 35-50.

Páez Tomás Coord. (2019), Latinoamérica Democracia y Autoritarissmo, 2da Ed. Edit Kalathos. España.

Páez. Tomás, (2024), The Venezuelan Diaspora Strategy, in editing process

— (2021). The strategy of the Venezuelan Diaspora: Collaboration, Representation and Reconstruction of Venezuelan People in Colombia, Latin America and the World. En V. Bravo y M. de Moya, (Eds.). Latin American Diasporas in Public Diplomacy (235-258). Londres: Palgrave Macmillan.

— (2022a). La Voz de la Diáspora Venezolana, 3ª edición. Bogotá: Unión Editorial Colombia.

— (2022b). La diáspora venezolana: un activo para el desarrollo y configuración de una nueva geografía de Venezuela. En La Transversalidad del ejercicio geográfico en Venezuela (109-122). Santiago de Compostela: Universidad de Santiago de Compostela.

Páez, T. y Phelan, M. (2018). Emigración venezolana hacia España en tiempos de revolución bolivariana (1998-2017), RIEM. Revista Internacional de Estudios Migratorios, 8(2), 319-355.

Páez, T. & Hidalgo, M. (2023). Spanish migration to Venezuela: the circularity of Canarian human capital (1940-2022), Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política, Humanidades y Relaciones Internacionales, year 25, no. 54. Third quarter of 2023. Pp. 625-651. ISSN 1575-6823 e-ISSN 2340-2199 https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/araucaria.2023.i54.29

Rey González, J. C. (2011). 2Huellas de la inmigración en Venezuela. Entre la historia general y las historias particulares2. Caracas: Fundación Empresas Polar.

Robertson, S. L. (2006). Brain drain, brain gain and brain circulation. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 4(1), 1-5.

Saxenian, A. (2005). From brain drain to brain circulation: Transnational communities and regional upgrading in India and China. Studies in comparative international development, 40(2), 35-61.

Torrealba, R., Suárez, M. M., & Schloeter, M. (1983). Ciento cincuenta años de políticas inmigratorias en Venezuela. Demografía y economía, 17(3), 367-390.

Tung, R. L. (2008). Brain circulation, diaspora, and international competitiveness. European Management Journal, 26(5), 298-304.

[1] Venezuelan Diaspora Observatory (ODV): (2024) Study on the Propensity for Political Participation of the Diaspora.

[2] Páez Tomás (coord.) (2015), La voz de la diáspora. Edit. La Catarata. España

[3] The reports prepared by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights are explicit regarding the violation of the human rights of Venezuelans in general and the diaspora in particular

[4] President Nicolás Maduro, at the United Nations, stated in the meeting in which there were representatives of the countries that at that time received tens of thousands of migrants that the diaspora did not exist.

[5] A recent study by the CATO Institute shows, in the area of delinquency and crime, data contrary to the arguments of political leaders in the United States. Testimony of David J. Bier: Associate Director of Immigration Studies at The Cato Institute. The House Committee on Oversight and Accountability Subcommittee on National Security, the Border, and Foreign Affairs. April 16, 2024

[6] ODVdiaspora.org. The Observatory’s website has information on the observatory network and documents and multimedia presentations

[7] The first edition presents the distribution of the diaspora by continents and countries. Páez T. Coor. (2015) The Voice of the Venezuelan Diaspora, Edit. La Catarata. Spain.

[8] The first weekly TV and radio program dedicated to the diaspora was broadcast through the pioneering radio broadcasting station in Venezuela, after its closure through the Internet using its platform and currently through the Observatory’s YouTube channel. We opened a new space that lasted a year and a half, “diaspora and environment” in which environmental organizations participated, in the face of the destruction of the Venezuelan environment. Both programs were broadcast by other media in Venezuela and Florida.

[9] The ODVdiaspora.org website contains the fundamental information of the project.

[10] The agreement of the organizations, the Observatory (ODV) and IOM that have culminated in Conceptual Notes, the alliance with the Central University of Venezuela and the Association of Executives and the Chamber of Industrialists of the Carabobo State. etc

[11] The demands made by the affected companies: Conoco Philips, Critalex, among others.

[12] The Law of Communal Councils, Law of Social Comptrollership, Law of Communes, Law of the Communal Economic System and the Law of Popular Power.

[13] Advisory referendum on the essequibo claim held on December 3, 2023

[14] Páez Tomás (2018) https://www.elnacional.com/noticias/columnista/diaspora-recuperacion-democracia_216518/

[15] Ibid. 2024. Study political participation and diaspora.

[16] There are abundant references to parliamentary pronouncements, mobilizations, complaints, and meetings that corroborate what has been said.

[17] Study carried out among diaspora organizations. IOM-ODV, in editing process.

[18] https://latinno.net/es/case/19105/ NYT: https://www.nytimes.com/es/2017/07/16/espanol/america-latina/los-venezolanos-acudieron-masivamente-a-votar-contra-la-reforma-constitucional-que-impulsa-nicolas-maduro.html

[19] Statement by the President of the Supreme Court of Justice. See also. https://www.refworld.org/es/ref/countryrep/icjurists/2017/es/127143

[20] Website: ODVdiaspora.org

[21] ODV-IOM. (2023) Diaspora Organization Management Manual. Study results.

[22] Link to the map of Venezuelan diaspora organizations:https://iom.maps.arcgis.com/apps/instant/interactivelegend/index.html?appid=640084b2d755474f859dbb5f7482559d

[23] The experience has been collected in the preface of the 2nd edition of the Voice of the Diaspora study. Venezuela. Edit El Estilete 2017 and in the book in the process of printing: “Diaspora Governance Strategy” (2024)

[24] The preface to the second edition of the study, published in Venezuela in 2017, includes the work carried out with the organizations the European Parliament and the Euro-Latin American Parliament

[25] The ODV presented the global project: https://www.globaldiasporaweek.org/

[26] The Study is in the editing process

[27] The project being developed includes the migratory experiences of Spaniards and in particular of Canary Islands, Galicians and Basques.

[28] Páez Tomás Coord. (2019), Latin America Democracy and Authoritarianism, 2nd Edition. Edit Kalathos. Spain.

Documentaries that have won awards or have been offered by large companies. The experience of AMAZINE already in the third call, transmitted by diaspora organizations in the world.

[30] The former Vice Minister of Venezuela used that expression at a meeting of Latin American presidents.

[31] From the first study to the most recent one completed and in the editing process, the response of the majority of Venezuelans in the diaspora indicates their commitment and willingness to participate in the recovery process of Venezuela

[32] The two reports prepared by the United Nations Mission of Independent Experts largely corroborate what was said.

[33] In 2018, a meeting of diaspora organizations in European countries was held in the city of Frankfurt.

[34] Statements by the former president and subsequent statements by other presidents confirm this.